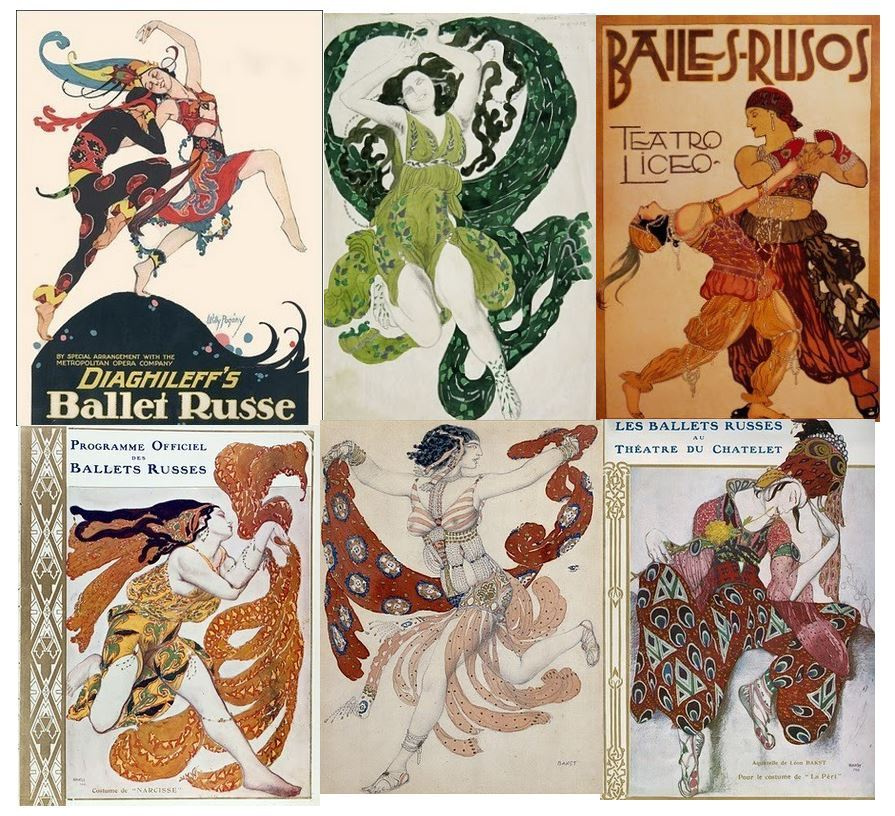

It Was the Ballets Russes That Influenced the Art of Fashion Internationally

Ballets Russes equally a driving forcefulness of a new aesthetic of the 20th century

The Ballets Russes (the Russian Ballet), an contained dance visitor, agile betwixt 1909 and 1929, was founded by the flamboyant Russian-born impresario Serge Diaghilev (1872−1929). By integrating gimmicky music, new approaches to dance and choreography, modern stage and costume design, and publicity he encouraged the artistic experimentation and collaboration of composers, choreographers, painters and publishers and unleashed a torrent of creative activity in European theatre. Ballets Ruses placed the formerly moribund art of ballet into the Modernist framework of early 20th century design and civilisation and formed a new aesthetic of the era.

Russian designers Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benoit and Nicholas Roerich provided the sumptuous and exotic spectacle of the start performances while other artists joined Diaghilev subsequently on—among them, an Avant-garde painter Michel Larionov and a neo-Primitivist Natalia Goncharova, Cubists Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, Fauvists Henri Matisse and André Derain, Surrealists Giorgio de Chirico, Joan Miró and Pavel Tchelitchev, a muralist José Maria Sert, and Orphists Robert and Sonia Delaunay.

When Diaghilev conceived of the Ballets Russes, he hasn't got whatever clear idea how performances should look like. Only he was pretty sure that they have to astonish, amaze and shock the audience. So, he needed the boldest choreographers, the most wonderful dancers, and the all-time artists indeed to create costumes and scenery sets never seen at theatres before.

Fortunately, it was time when practices flourished and Diaghilev could choose among a perfect set of artists who were able to switch betwixt magazine graphics and religious frescoes and between small illustrations and the vast theatrical backdrops.

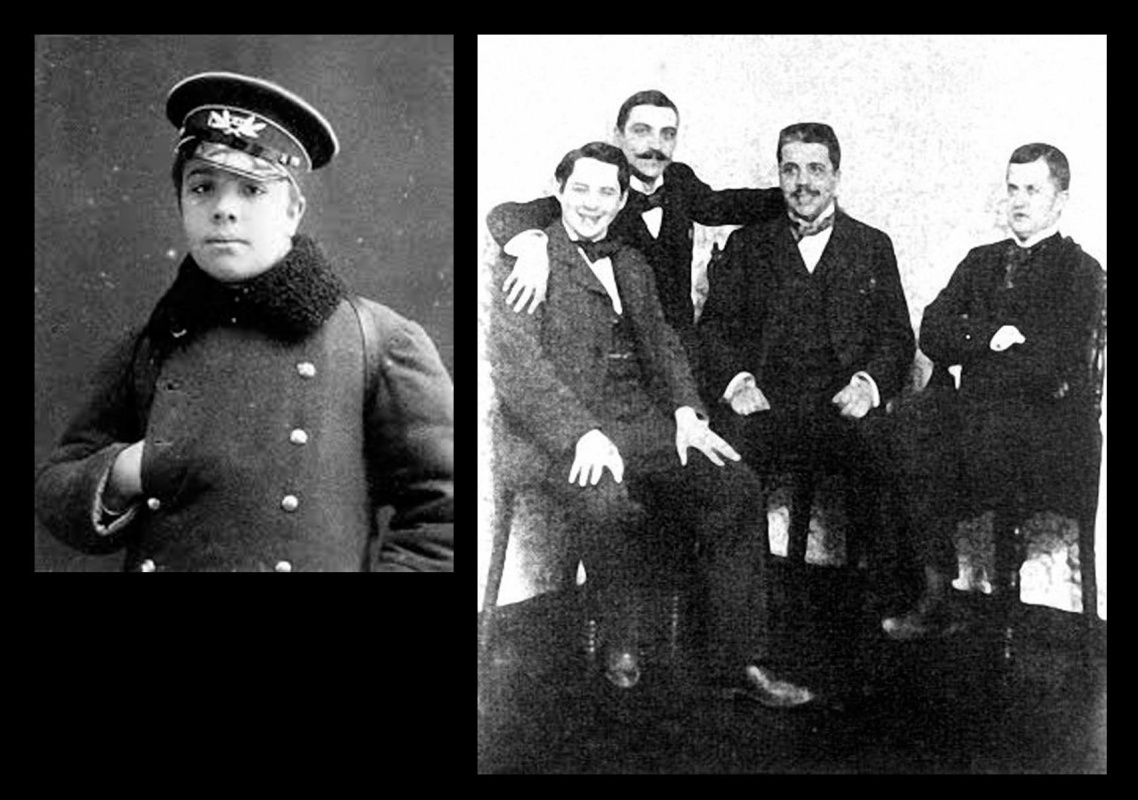

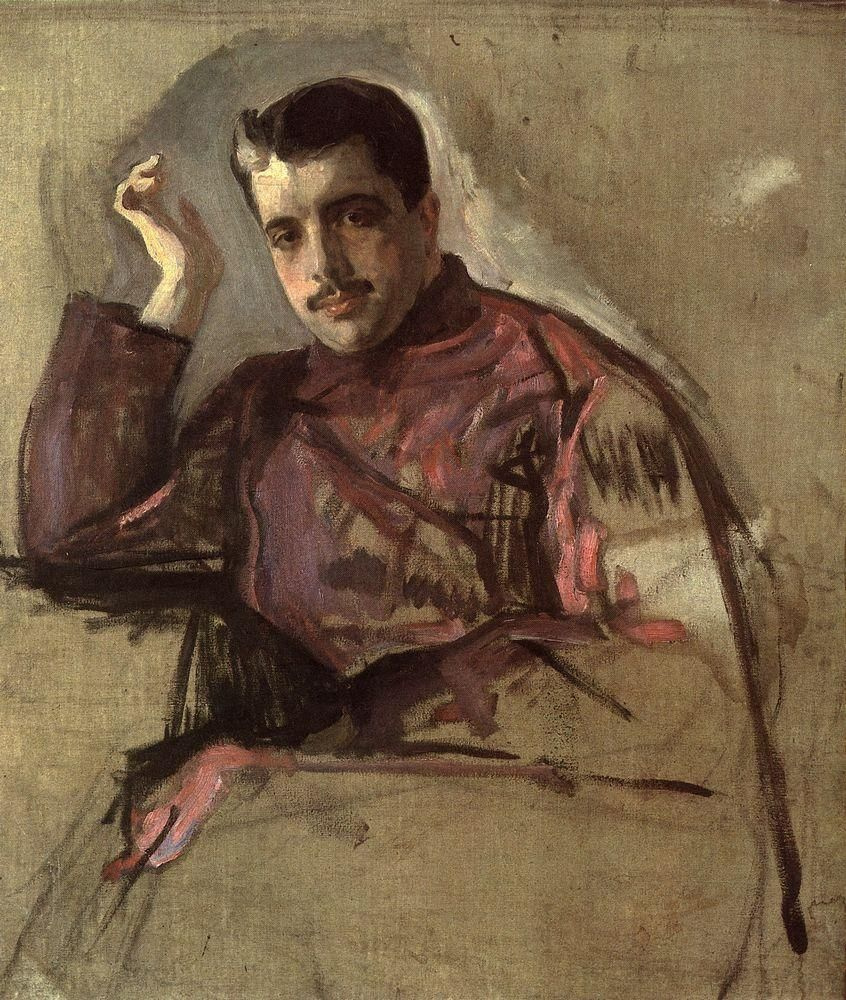

Serge Diaghilev

Diaghilev did not option artists by their theater portfolios but rather evaluated their exhibitions at art galleries. Although he never took lessons in art just had a constabulary caste instead, he had a keen eye and a high level of civilization. He was born and raised in a family with a long line of noblemen. Their house in Perm was called the "Perm Athens", and city intellectuals and artists gathered there each Thursday. These evenings were always full of art: music, singing, and domicile performances. When the family moved back to St. Petersburg, he studied law at the academy and music composition at the conservatory simultaneously.

He was too introduced to a circle of art-loving friends who chosen themselves The Nevsky Pickwickians. Aided by Alexandre Benois, one of its members, he learned much of Russian and Western art. In two years, Diaghilev had voraciously absorbed into his fine art studies, fifty-fifty traveling abroad, and came to be respected as one of the most learned of the group.

one. Sergei Diaghilev in his youth. 2. Co-founders of the art journal "Mir Iskusstva": Konstantin Somov, Walter Nouvel, Sergei Diaghilev and Dmitri Filosofov. Photo: belatedly 19th century, credit to: lafrimeuse.com.

Diaghilev, and then thirty-5, became one of the most of import people in the art world of Leningrad. With his friends, a loosely organized fraternity of artists, musicians, critics, and other writers, he fix himself the goal of liberating Russian artistic civilization from the narrow political dictates ( , nationalism, social criticism) that had dominated information technology since the 1860s. The group's well-nigh influential projection was its art journal, "Mir Iskusstva" (The World of Art, 1898−1904), initiated, co-founded and edited past Diaghilev. Existence appointed as a chief editor to it, he besides published his own art critics articles from fourth dimension to fourth dimension.

The magazine has become a platform for the fine art of the European fin de siècle and provided readers with a valuable opportunity to meet new protagonists of the world'due south art scene of the 24-hour interval. "Mir Iskusstva" was instrumental in converting Russian painting from an exhausted to the freer, more imaginative symbolist style of the early twentieth century.

Diaghilev also began to paint. Yet he became neither a lawyer, nor a composer, nor a painter but remained an amateur in all these fields, or equally he himself said, a "corking charlatan". His unique managerial talent adult when he melded his varied interests and cognition to create the globe's most circuitous and genuine art-workshop. He was, however, too contained and extravagant, too rebellious to be accepted in Russia, and in 1901 he was fired from his job as advisor to the regal theater. He was offended and in a demonstrative fashion refused to keep on editing the "Almanac of Imperial Theatres", which he turned from a dry out edition into an illustrious art magazine.

Diaghilev'south international fame spread far and wide with the arrangement of an extraordinary exhibition of four thou Russian historical portraits in St. Petersburg's Tauride Palace in 1904. Information technology attracted forty-five thou visitors. "It must exist emphasized that Diaghilev," notes Modris Eksteins, a famous Canadian historian specializing in modern civilization, "the budding experimentalist who was to become manager-extraordinaire of the 'modernistic spirit,' lauched himself from the foundations of the Russian by".

-

"Mir Iskusstva" fine art journal embrace, Yakunchikova, 1899.

-

"Mir Iskusstva" art journal, title page, Bakst, 1903.

Ballets Russes. Season 1909

Being rejected by Russia, Diaghilev began bringing Russian art to the West and chose Paris every bit his base. He arrived at that place in 1906 and organized a blockbuster exhibition of Russian painting and sculpture at the Petit Palais. He saw his personal mission in redeeming a declining old civilization through confrontation with the elemental Russian arts. "Russian art will not just brainstorm to play a function," he wrote before his first Paris exhibition, "it will also become, in actual fact and in the broader meaning of the world, one of the principal leaders of our imminent movement of enlightenment".

During 1907, he presented five concerts of Russian music, well-nigh of it unknown to Europeans at the fourth dimension, and in 1908, he organized a triumphant production, the first in the West, of Modest Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, starring Feodor Chaliapin at the Paris Opéra.

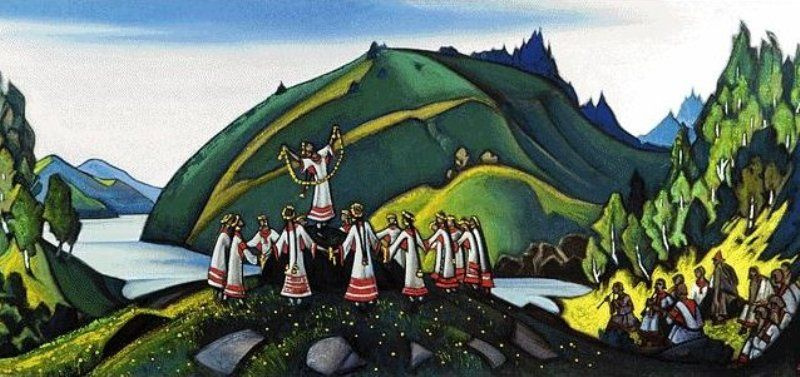

He made a real breakthrough on 19 May, 1909, when opened the Ballets Russes (Russian ballet) at the Théâtre du Châtelet. With the get-go-night performance, the Polovetsian Dances from the "Prince Igor" (Act II) opera past Borodin, the Paris audience was transported to a wilder world of Russian history set in the steppes of Central Asia. Western public was delighted by a stiff, powerful and attractive Adolph Bolm as the Master Warrior in Michel Fokine'southward choreography. People were longing for male protagonists in ballet, for male dancers were relegated to minor roles during much of the 19th century. The audience was too amazed by Nicholas Roerich's set featuring unusual Russian folk art and nomadic tribal history.

-

Pierre Choumoff, Adolph Bolm, Polovtsian Dances, 1909.

-

Nicholas Roerich, The Polovtsian military camp , 1909.

The ballet had a sensation success. The company Les Ballets Russes conquered Paris and afterward preformed in most major cities throughout Europe (although never in Russia) and in North and S America from 1909 to 1929 until the untimely decease of Diaghilev.

The stage designs for the operas and ballets brought the exoticism of Russian culture to a wider Western audience, and with it the work of Russian artists and designers such as Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov; century's nearly innovative choreographers including Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, Léonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska and George Balanchine; composers Igor Stravinsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Nicholas Tcherepnin; and dancers such as Tamara Karsavina, Anna Pavlova, Adolph Bolm, Serge Lifar and Vaslav Nijinsky. Through the collaboration of the all-star fine art cast Diaghilev was able to bring to life a new vision of the Slavic, oriental, , romantic and later constructivist elements of Russian culture.

Léon Bakst

The characteristic bright colors, décor and costumes produced by Leon Bakst and Alexander Golovin for the ballet performances that were given in 1910 — Scheherazade, Cleopatra, and the Firebird — were enriched with exotic Oriental motifs and influenced both fashion and interior design in Europe.

Ballets Russes did more to transform the everyday bourgeois environment than whatsoever other preceding art trend. Leon Bakst inspired style designers, such as Paul Poiret, Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli. Fine art and fashion magazines, including Vogue, Comœdia Illustré and La Gazette du Bon Ton, published pre- and mail-performance articles, photographs, drawings and paintings, which fueled the stage-to-street dialogue.

Detail of 'Robes manner Bakst réalisées par Paquin', 1913. Comoedia Illustré, no. 15, 5 May 1913, 718−19. Printed paper Private Collection.

"The Ballets Russes became finely attuned to Parisian fashion, responding to the tastes and trends, and adapting the latest styles for its artistic presentations," wrote Mary E. Davis, professor and chair of Example Western Reserve'southward Section of Music, exploring this high culture exchange. "The boundaries betwixt phase and street collapsed… haute couture met high culture on a new ground."

The merger of art and fashion created a setting in which audience showed their attire from their seats similar to dancers that performed on stage in costume. Diaghilev, with the help of Bakst's costuming, brought a new and modern look into the early 20th century fashion world. And soon the well-nigh adventurous women were wearing harem pants, head wraps and tunics.

Fancy wearing apparel costume, 1911

Paul Poiret (French, 1879−1944)

Seafoam green silk gauze, silver lamé, blue foil and blue and silver coiled cellophane string appliqué, and blue, silver, coral, pinkish, and turquoise cellulose beading

Photo courtesy of The Met Museum

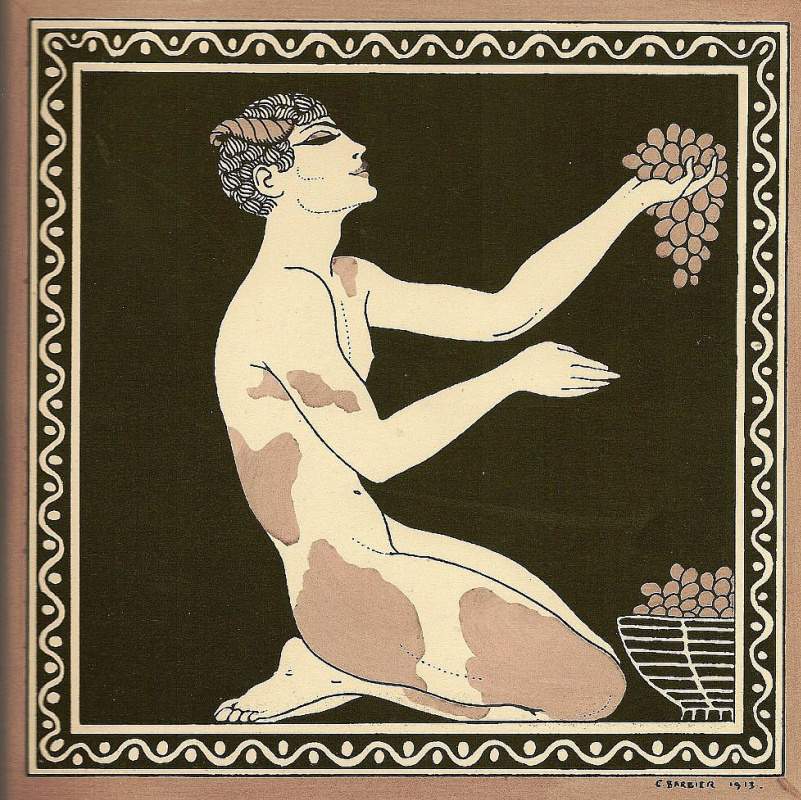

The Afternoon of a Faun

Two of the nearly defiant and provocative ballets were performed by Ballets Russes between 1912 and 1913. The seeds of controversy were planted by Diaghilev himself. He thought that the main choreographer, Michele Fokine, has run out of ideas and encouraged his lover Nijinsky to begin his choreographic career. Vaslav produced three ballets—The Afternoon of a Faun, Jeux, and The Rite of Bound—that had nix in common with academic schoolhouse and were admittedly reverse to what accept been chosen ballet earlier. In that location weren't any lovely, noble, three-dimensional shapes of the bookish ballet, the 5 positions of the legs and arms, the turned-out feet. All of these gone.

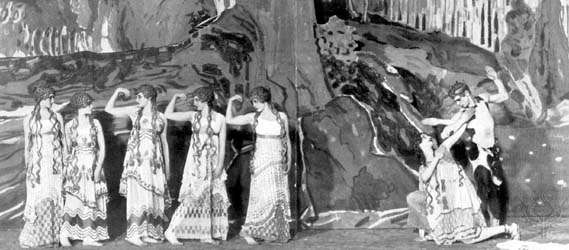

Vaslav Nijinsky (far right) performing as the Faun in the premiere of the Ballets Russes'due south production of L'Après-midi d'united nations faune (The Afternoon of the Faun) at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, 1912. Edward Gooch—Hulton Archive/Getty Images

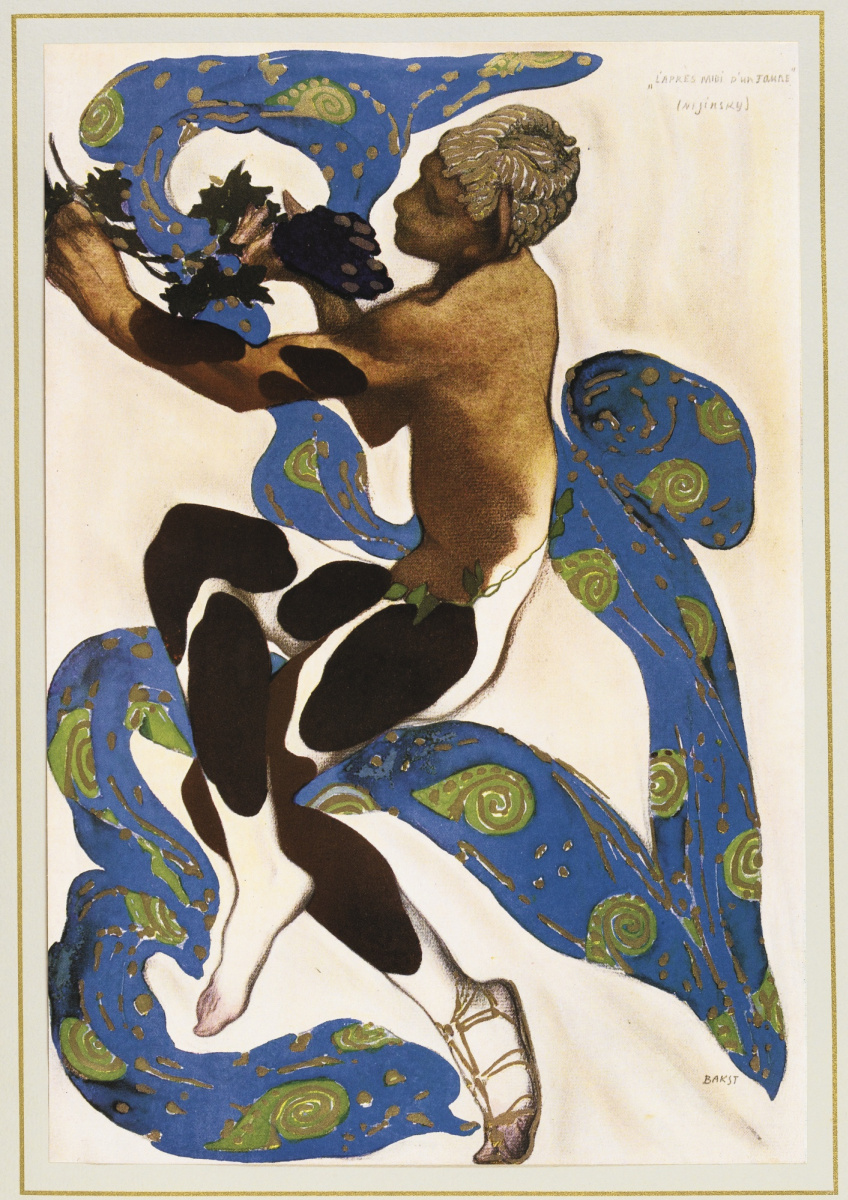

According to Nijinsky's choreography in The Afternoon of a Faun, the dancers moved beyond the stage in profile equally if on a bas relief, slicing the air like blades. His aim was to reproduce the stylised look of the ancient artwork on the phase. The original idea was developed by Diaghilev, Nijinsky and Bakst and was inspired by decorative painting on ancient Greek vases and Egyptian and Assyrian frescoes, which they viewed in the Louvre museum. In portrayal of the faun, played by Nijinsky himself, Vaslav managed to reproduce exactly the figure of a satyr shown on Greek vases.

Information technology was a brusque, eleven-infinitesimal 2-dimentional ballet, showing a salacious story about a faun, who afterwards flirting with six nymphs, chased the primary one just failed to agree on to her. Dreaming of her, he only warmed his passion and finally allow out his sexual desire in a transparent nymph's veil on a loma where he had an afternoon nap in the beginning of the performance.

Léon Bakst worked closely with choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky to attain the frozen poses of Greek dancers seen in Antiquarian art. He produced an accordingly layered, darkly glowing Symbolist ready pattern, against which the dancers postured in their frieze-like positions. The nymphs' flowing costumes made of transparent veils were at the same fourth dimension anchored by almost architectural underskirts in metallic pleated fabric. They were fabricated in deliberate contrast to the sinuous, form plumbing fixtures tights—the only detail of the fauna-like costume worn by Nijinsky every bit the Faun.

The languorous and celebrated musical score for this short ballet was written by Debussy in 1894. Planned originally equally merely the first part of a trilogy, he somewhen understood that this i slice is enough to brand a musical evocation of Stéphane Mallarmé's verse form "Afternoon of a Faun," in which a faun—a half-man, half-caprine animal creature of ancient Greek legend—awakes to revel in sensuous memories of forest nymphs.

On the opening night of May 29, 1912, the performance was met on the border of applause and booing. There was silence as it finished. To save the ballet, Diaghilev announced that it would be repeated. The second fourth dimension the audience applauded. However, a strikingly different response to the performance appeared in critical reaction the next twenty-four hour period.

Auguste Rodin, the progenitor of modernistic sculpture and the revered 72-yr master, defended it. He attended the premiere and stood upwards to cheer it. The post-obit morning, a forepart-page newspaper editorial signed by Rodin praised the "deliberately awkward" and "jerky" movement. Nijinsky posed for Rodin several days later. The strong profile of the sculpted bellow pays tribute to Nijinsky'due south choreographic style, which mimicked Greek bas-relief sculpture.

The Rite of Jump

In The Rite of Spring, dancers were hunching over and hammering their feet into the floorboards. The approach to the operation was analytic, the look "ugly," the emotions discomforting.

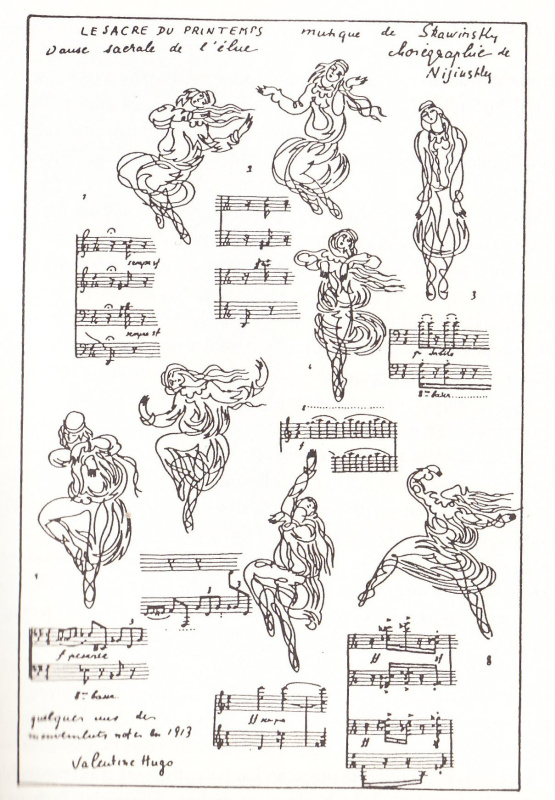

Innovative music past Igor Stravinsky magnified bear upon of rough folk slavic costumes and bright scene designs past Nicolas Roerich and of modern choreography past Nijinsky. In particular, Igor Stravinsky's now-famous primitive and syncopated passages, made the audition erupt with a anarchism at its premiere on the 29 May 1913. Shouting turned into fist fighting and the police force had to be chosen. Stravinsky retreated backstage, while Nijinsky connected bellowing counts to the dancers. Later, the audition revealed that it had not merely been the music that had ready the audience off, only the choreography and the costumes. Afterwards, Diaghilev claimed that the scandal was only what he wanted.

Higher up: Valentine Gross Hugo, Drawing of Marie Piltz in the "Sacrificial Dance" from The Rite of Spring, Paris, 29 May 1913, Published in Montjoie! magazine, Paris, June 1913.

through

The First Globe War put an end to opulent and lavish fantasies. During the war years, theaters were shuttered and the Ballets Russes struggled; frivolity went out of fashion. Despite all troubles and difficulties, Diaghilev wouldn't want his ballet exist in the doldrums. So, he turned to Modernism, embracing the art's border. First, though, honoring the historical traditions modernists had emerged from.

In 1914, Léon Bakst designed costumes for one-act ballet, The Legend of Joseph, in the manner of Italian painter Paolo Veronese. "The ordinarily known biblical legend is interpreted in the manner it may have been done by sixteenth century artists," Bakst later wrote. "The luxury of the flamboyant oriental colours will pass, as information technology were, through the artistic vision of the ."

-

Leon Bakst, Costume design for Potiphar's wife in the ballet The Legend of Joseph, 1914

-

Leon Bakst, Costume design for Potiphar in the ballet The Legend of Joseph, 1914

José Maria Sert

In two years, Diaghilev deputed Spanish muralist José Maria Sert to blueprint Diego Velázquez-inspired costumes for Las Meninas (1916)—a functioning intended to thank Spain for sheltering the dance company during World State of war I. Dancers wore dresses inspired past those in Velázquez's approved 17th-century Spanish purple portrait, foregoing tutus for corsets and broad, brocaded skirts.

1916, Las Meninas. Music by Gabriel Fauré. Choregraphy by Leonide Massine. Sets by Carlo Sokrate. Costumes past José-Maria Sert. Photo: Tamara Grigorieva, Irina Zarova, Alberto Alonso. Georges Skibine and Nicolas Ivangin for Las Meninas, 1916

Natalia Goncharova

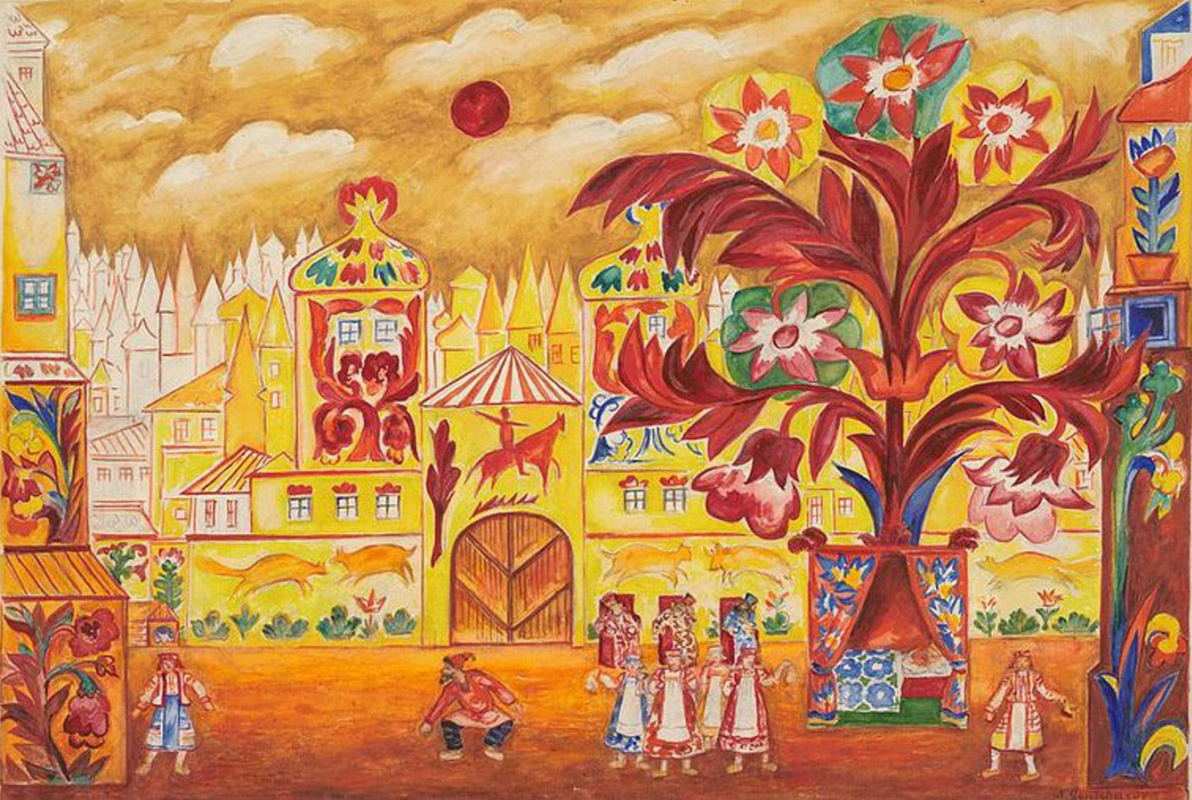

Before Diaghilev moved to Paris, he visited a large-scale Moscow retrospective on Goncharova—a prominent member of the Russian , inspired by folk fine art and in equal measure. He was amazed by her piece of work and commission her sets and costumes for many ballets including Le Coq d'Or ( The Aureate Cockerel) (1914).

An extraordinary mod painter, Natalia Goncharova drew her complex neo-primitivist fantasy from a Russian fairytale adjusted and rhymed by Aleksandr Pushkin's in his 1835 poem "The Tale of the Golden Cockerel". Visually, she drew inspiration from the assuming outlines of Russian icon painting and the abstruse patterns of peasant embroidery, using tradition to fuel the modern. Although designed in a Modernism style, The Golden Cockerel looked to a earth already disappearing, presently to be imagined only outside Russia.

-

Natalia Goncharova, Costume design for the Opera-Ballet "The Golden Cockerel", 1914

-

Natalia Goncharova, Costume blueprint for the Opera-Ballet "The Golden Cockerel", 1914

Michel Larionov

Natalia Goncharova's husband, Michel Larionov, was ane of the prominent Futurists, exhibiting in all the leading exhibitions in Russia, as well as many abroad, including displays managed by Diaghilev in Paris and in Munich.

Larionov with Goncharova joined Diaghilev in Lausanne in 1915. Michel became Diaghelev's close and frequent collaborator: he consulted impresario in art, was an occasional choreographer, and wrote several ballet scenarios. He was commissioned to design for Soleil de minuit ( Midnight sun) (1915); the unrealised Histoires naturelles (1916); Contes russes (1917); Chout ( The Tale of the Buffoon) (1921); and finally Le Renard (1922).

Lydia Sokolova, the company's outset English ballerina and the main character dancer, said of Mikhail Larionov's costumes for Chout, a ballet by Sergei Prokofiev: "Although the costumes were vivid in colour and wonderful to wait at, they were appallingly uncomfortable."

-

Michel Larionov, Costume for a buffoon'southward wife, "Chout", 1921. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

-

Michel Larionov, Costume for a soldier, "Chout", 1921. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

During 1916−1919, the visitor toured popular performances to new audiences in North and Southward America. Yet at that place were long periods in Europe without any shows, in which the company experimented with new original ideas. Lionize Massine, a new lover of Diaghilev, emerged as a talented new choreographer, drawing on influences from the countries of his travels, notably Italy and Spain.

Diaghilev's fame introduced him to the wider earth of the artists and led to him commissioning painters such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Georges Braque, José Maria Sert and Giorgio de Chirico to design costumes and scenery for a number of his productions in the years that followed.

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso was introduced to Diaghilev by his friend, a young writer Jean Cocteau in 1915, and their acquaintance lead Picasso to his first ballet commission, the Parade (1917).

The war made many scrambling out of Paris, and Picasso decided to move to Rome in the leap of 1917 where the Ballets Russes were rehearsing and performing. He stayed in that location at the Hotel de Russie with Cocteau, made friends with Leonid Massine and met Igor Stravinsky, and the 2 became friends for a long-long time.

It was in Rome that Picasso met a Ukrainian-born ballerina Olga Khokhlova, who danced in Parade, and he married her in 1918. In 1921, she would give birth to their son, Paulo. And although they separated after x years together, they were officially married until her death in 1955 for Picasso didn't want to divide his manor with her.

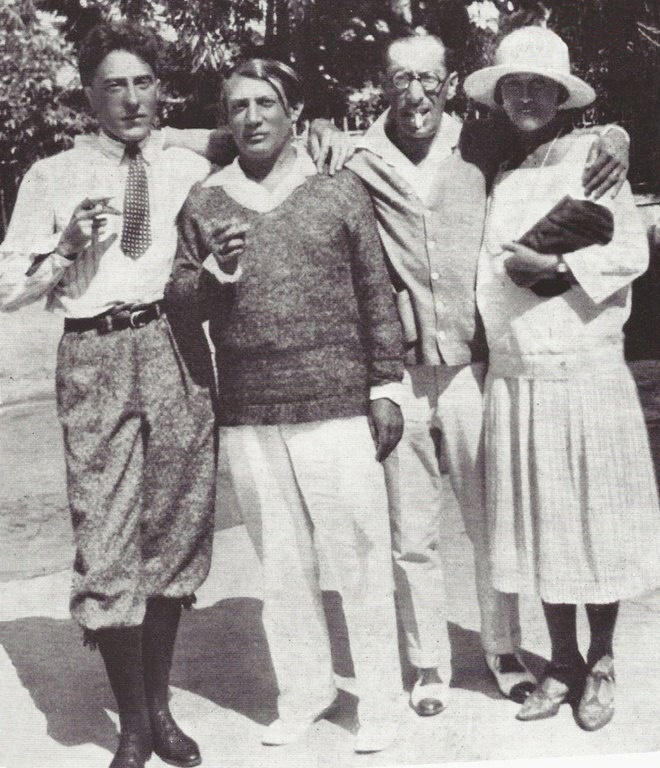

Above: Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Igor Stravinsky, Olga Khokhlova in Antibes, 1926.

In addition to the cubist costume designs for Parade, Pablo Picasso too designed a wonderful drib pall that was very much in his new neo-classical mode. It illustrated a group of performers at a fair consuming their lunch before a performance. The backcloth scene was a relief for the audition—it has blunted their worries well-nigh Picasso'due south fancy cubic tricks. But when information technology went up, their anxiety came back at full…

Picasso'southward big backcloth for Parade measures 16.40 m by x.50 thou and weights 60 kilos, making information technology the largest of his works. The Italian artist Carlo Socrate helped to fill the sheet with paint. Information technology is now displayed in the Middle Pompidou-Metz.

Left: Pablo Picasso and scene painters sitting on the forepart cloth for Parade, photograph past Lachmann from Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Parade

Parade is a one-act ballet surviving until nowadays and it has nothing to practise with a 'parade' in its nowadays pregnant. It tells the story of a modest travelling theatre group in a Paris streets presenting a parade—a little preview to lure the passers-by into attention their testify. The managers endeavour to convince the oversupply to come up run into the show. The performance includes French and American managers, a Chinese magician, a lilliputian American girl, a equus caballus, and two acrobats. The Picasso's Parade was a kind of mixture of boggling cubist sculptures and costumes produced in different art styles.

Satie's music for the Parade was exotic and eccentric. In add-on to jazz, included for a ballet music score for the start fourth dimension, he peppered it with the sounds of typewriters, sirens, airplane propellers, ticker tape and a lottery wheel. Cocteau, who wrote the ballet'south scenario, was indeed searching to kindle another riot, similar that at the premiere of The Rite of Spring, in Paris, four years earlier. And Cocteau got it! But the booing that Parade received on opening dark on May xviii, 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris was mostly for Picasso'south Cubist designs, not for the typewriter in the pit.

Reconstruction of the ballet Parade past the trope of Teatro dell'Opera de Rome. Set design and costumes by Pablo Picasso, choreography Léonide Massine.

Picasso's 7 costumes created for Parade combined different fine art styles: for managers, where the technical contribution of Fortunato Depero is essential; African fine art for the horse; the Russian folk tradition of Leon Bakst in the two acrobats. The Chinese acrobat, meanwhile, refers to Orientalism revisited in a futuristic vein. For the American girl, Picasso uses a little crewman's dress.

The premiere of the ballet produced a number of scandals. As soon as the curtain raised, the tumult in the hall increased, the screams fused: "Go to Berlin! Sales boche!" In those times of war and thrift, the public was hostile to extravagance and merely the presence of the famous French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in uniform, wounded, the shaved caput, a scar on the temple and a cast around the head, prevented raging spectators from attacking the perpetrators. Nigh causing a riot at first, the audience were drowned out by enthusiastic applause in the end.

Apollinaire, the greatest defender of Cubism, was one of the first to have supported Picasso in his debut. In the programme notes for the premiere, he said that the Parade had "a kind of surrealism" ("une sorte de surréalisme"), thus coining the discussion three years earlier emerged as an art movement in Paris.

Cocteau got his scandal, although not in the way he was anticipating. Afterwards the premiere in Paris, Satie sent an insulting postcard to the critic Jean Poueigh, who published a hostile review of the ballet even though the music itself wasn't actually mentioned. It read: "Sir and honey friend — y'all are an arse, an arse without music! Signed, Erik Satie." Poueigh brought a libel case confronting Satie and won.

The point was that Satie sent him a postcard without an envelope. Poueigh'due south reputation was damaged: the words may have been read by a postman and a concierge! Satie was sentenced to 8 days in prison with a fine of 100 francs, and 1,000 francs in amercement, despite a spirited defence by Cocteau in the court. Actually, the writer was repeatedly yelling "arse" defending his friend in the court. Then, he was also arrested and beaten past the police. Satie appealed against the judgement, the sentence was suspended, and the Princesse de Polignac helped Satie to pay his fine.

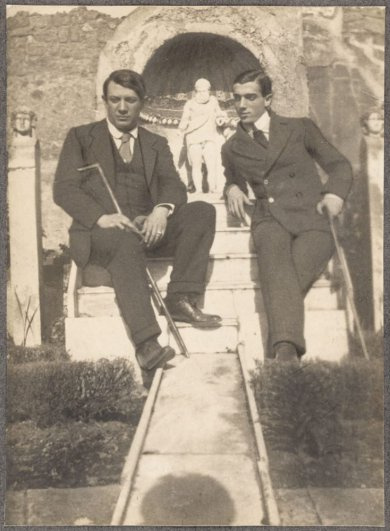

Picasso, Stravinsky, Massine and Cocteau visited Pompeii during rehearsal catamenia of the Parade. In Naples they were introduced to folk art and the commedia dell'arte — an improvised kind of popular comedy in Italian theaters in the 16th-18th centuries, based on a set of characters. In it, actors adapted their comic dialogue and action according to a few basic plots (commonly love intrigues) and to topical issues. The men were inspired by what they saw, and three years later, Picasso, Stravinsky and Massine premiered their new ballet, Pulcinella. Information technology was the ballet Picasso was most proud of.

Left: Pablo Picasso and Leonid Massine photographed past Jean Cocteau at Pompeii

Pulcinella

Reconstruction of the ballet Pulcinella past Europa Danse, 2007. Photo: Yard. Loginov

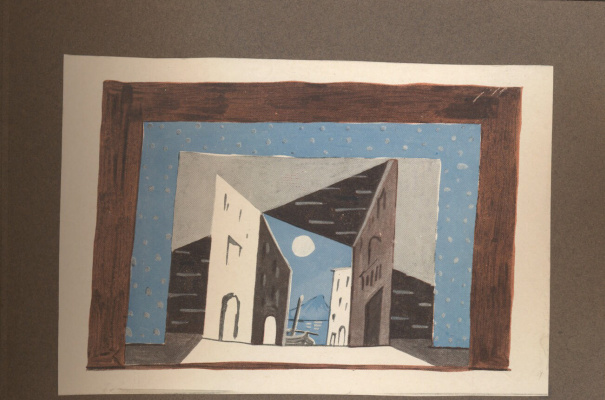

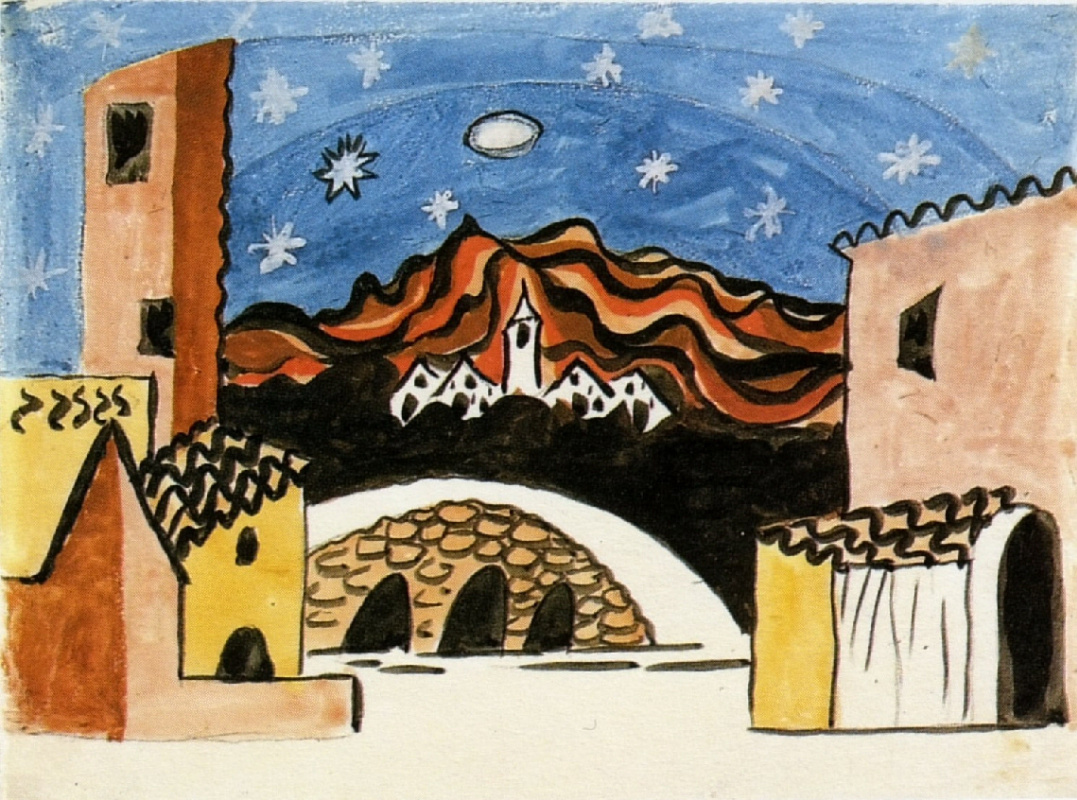

Picasso and his friends fell in love with Naples at first sight. Picasso wrote to his friend Guillaume Apollinaire that they discovered a metropolis of wonders, "one-half Spanish, half eastern", an "Arab Montmartre" and that "everything is easy here." Picasso based his sketches of the ready design for the Pulcinella ballet on the sketches of the city made at plein air during his trip to Naples: the fountain of Neptune, the Place de la Bourse, Vesuvius smoking, seen from the district of Santa Lucia, the Umberto I gallery, the district of Sanità.

Fifty-fifty though Picasso made dozens of sketches to the scenery set in baroque way, he finally chose the ane close to Cubism, in bluish gamma. He abandoned the lavish bizarre extravagances and simplified the whole course to its utmost: an opening prospect, allowing to see the night sky betwixt houses with a large full moon, hanging over a boat in a harbor, was interpreted by him in a strictly cubist mode.

Above: Set blueprint for the ballet Pulcinella by Pablo Picasso, 1920. Museum of Picasso, Paris

For Pulcinella's costume pattern, Picasso drew inspiration from the eighteenth century models. He composed it of a traditional white tunic with a wide black belt and a soft lid. The mask covering his face was a masterpiece of synthetic cubism. It was inspired by similar masks used in Neapolitan theaters since the eighteenth century.

Left: Costume for the ballet Pulcinella by Pablo Picasso, 1920. Museo of Picasso, Paris

Le Tricorne

The same epoch inspired Picasso when he created costumes and sets for the ballets Le Tricorne (1919) and Cuadro Flamenco (1921).

The main protagonists of the ballets were the traditional Spanish music, songs and dances inserted into the music score by the composer Falla as was requested of Diaghilev.

The costumes for the Tricorne evoke the traditional Spanish costumes of the eighteenth century, to which Picasso added bold ornaments, lines and arabesques. He was inspired by paper dolls and small models used in haute couture—a universe discovered by Coco Chanel at the time.

Sonia Delaunay

In 1911, Sonia Delaunay, a Ukrainian-built-in artist, began to experiment with abstract patterns, producing artworks that epitomized the concept of Simultanisme (Orphism) or 'simultaneous contrasts'. In addition to paintings, she made collages, book bindings and apparel. By using colour in a bold, imaginative mode and by employing simple geometric forms—circle, square, rectangle, and triangle—in conjunction with color, she was able to suggest different depths of planes and a sense of movement in her work. She spent the residue of her career exploring how forms and colours interact, specially in cloth.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, she moved to Madrid and Portugal. Sonia had studied there dances such equally flamenco and tango before meeting Diaghilev. In 1917, he requested her to create costumes for the Ballets Russes revival of Cléopâtre (1918). And she did it brilliantly. Sonia Delaunay'a bold, bright, geometric designs gave gravitas to her budding fashion career. In a way, Diaghilev helped her to launch a career in pattern, especially mode.

Henri Matisse

Diaghilev produced Stravinsky'due south opera, Le Rossignol (The Nightingale), in 1914. Withal, the original opulent orientalist set and costumes by Benois were destroyed during the World War I and Diaghilev wanted to commission a new ballet version which, post-obit his successful engagements with Picasso and Derain, he hoped would be designed past some other major artist. He has chosen Henri Marisse and decided to persuade him to work on the production in 1919. Diaghilev was lucky—Matisse admired Massine'south choreography and fifty-fifty had a collection of exotic birds. Yet, Matisse had no theatre experience but this wasn't a critical bespeak for Diaghilev. He trusted Matisse level of fashion in art.

Matisse took the commission with enthusiasm. The story was based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairytale of the aforementioned name, Le Chant du Rossignol (The Vocal of the Nightingale) and Matisse was determined to produce a pattern different from the loftier-keyed exoticism associated with the Ballets Russes.

Henri Matisse, Léonide Massine and the mechanical nightingale from the ballet Le Chant du Rossignol, Monte-Carlo 1920. Photo by Joseph Enrietti. Credit to Victoria & Albert Museum, London

His backdrop was porcelain-white, his refined costumes were of light colors and based on traditional Chinese Ming court wearing apparel derived from Chinese ceramics and lacquer. The courtiers' costumes were elaborately tailored in silk, and Matisse himself decorated them with his own painting. Dancers in his costumes created the impression of a continuous pattern on the phase, equally if the audience was reading a scroll painting.

Matisse invented the animal-like cloaks for the mourners gathered around an sick Emperor which were among the most breathtaking of Matisse'south designs. They were fabricated from a white felt-like drapery lining material with appliquéd triangles and chevrons of navy blue velvet, inspired past the markings on Chinese deer.

Coco Chanel

Coco Chanel was a rule billow in life and piece of work. By 1920, she was famous, well-continued and wealthy enough to be noticed by Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Chanel happily joined his circle of creative groundbreakers and financed the revival of the Ballets Russes' scandalous pre-war striking, The Rite of Spring. She linked herself to the stage, not to mention her relationship with the married composer Igor Stravinsky—a scandalous affair in the winter of 1920.

Igor Stravinsky (third correct) and Coco Chanel (right) at a party.

Diaghilev took detect of Chanel's mod design aesthetic at the time. As a woman, Coco knew how painful it was for women being cinched into tight, wasp-waisted corsets and covered neck-to-toe in elaborately draped material. She chose to salvage them of this burden revealing the body's natural contours in comfortable, softened silhouettes.

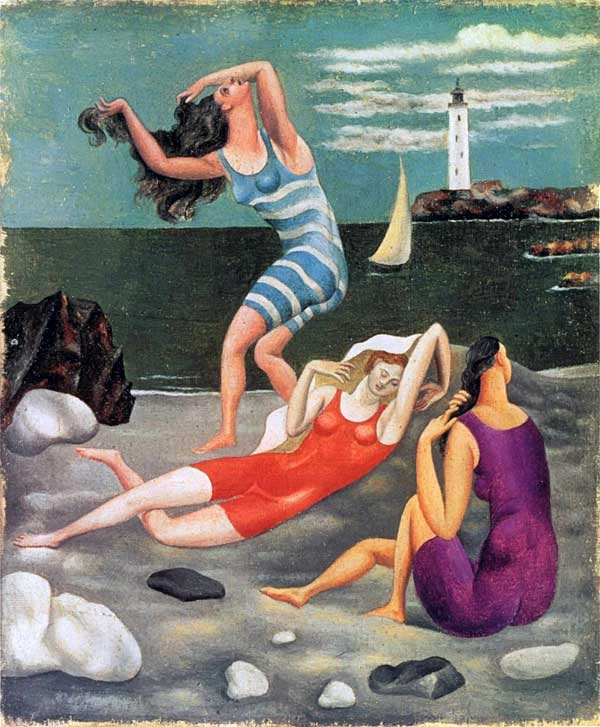

Her provocative bathing suits were as revolutionary as Cubism. These "sports dress" became instantly popular in the Reviera, and Diaghilev asked her to pattern costumes for his new gimmicky production Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) well-nigh the luxury locomotive that transported wealthy Europeans to Monte Carlo.

To a higher place: Chanel's clingy new bathing suits captured by Picasso in "Women Bathing" 1918.

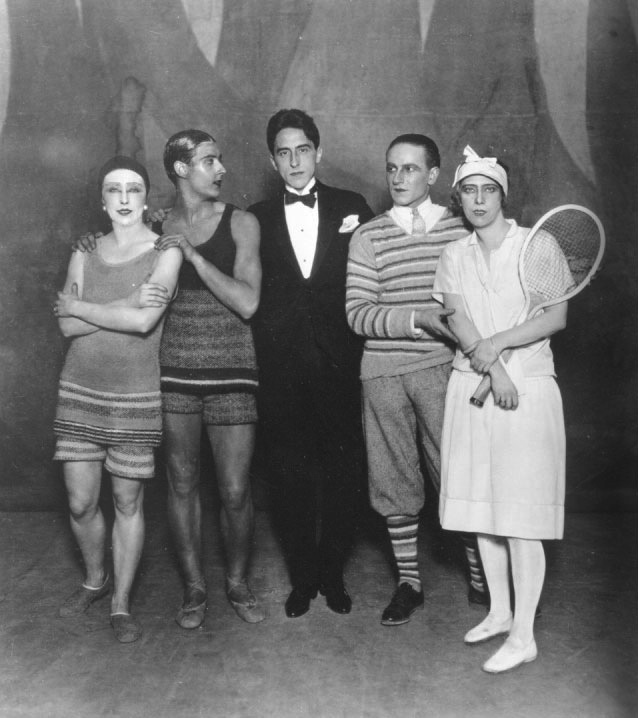

In 1924, Chanel created costumes to outfit the dancers of the ballet Le Railroad train Bleu, with libretto by Jean Cocteau and choreography by Bronislava Nijinska (Nijinsky's sister). They were based on Coco's own everyday designs—signature blackness bathing adjust, caps, accessorized with slippers and the Kodak cameras. This 'highly original' attire should fit a grouping of idle rich vacation-makers who take the brand-new tourist train due south to the Riviera. The satirical ballet poked gentle fun on vacationers and the audition loved information technology. Notwithstanding, the performers were less enthused.

Bronislava Nijinska, Anton Dolin, Jean Cocteau, Leon Wolzikowski and Lydia Sokolova on stage of Le Train Bleu, 1924. Photo: Sasha. Credit to Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The dance historian Sarah Woodcock writes that Chanel's loose-plumbing fixtures knit swimsuits were "potentially dangerous" for the ballet dancers. A male dancer would accept trouble keeping "a firm grip on his partner in the circuitous throws and catches." Hoop skirts cut dancers' shins and left them tottering during spins, and arched headdresses "slipped and were then impossible to adjust." To a higher place: Costume by Coco Chanel for Le Railroad train Bleu, 1924

As Tina Sutton wrote in "The Making of Markova" (biography of a cherished baby ballerina of Serge Diaghilev): "Consider poor Lydia Sokolova. Chanel presented her with a wool jersey bathing costume and rubber slippers that stuck to the stage. What could exist worse? The ballerina also had to wear oversized false pearl earrings, much similar the costume jewels favored by Chanel's affluent clientele, the very ones who would exist in the audience on opening night. The ear bobs were so large and cumbersome, Sokolova couldn't hear her orchestra cues. Leon Woizikowski fared no better. He had to master grand leaps while wearing his Chanel-designed golf knickers, shirt, necktie and striped long sleeve sweater; and Nijinska'due south tennis dress came complete with a full-size racket."Yet, Coco Chanel teased out the influence of fashion on art and fine art on style—a tendency that continues today.

The Prodigal Son—the concluding ballet of Serge Diaghilev

Diaghilev did non follow the prescriptions of doctors and in late 1920s, he suffered from severe pains in legs caused by diabetes. Thoughts of close death occupied his listen quite often. "Are all of us doomed to come up to an stop through decay? Or is there a take chances to be taken to heaven alive?" he in one case said. He knew that immortality is only possible through repentance in Christianity. And for Diaghilev, his concluding ballet Le Fils Prodigue (The Prodigal Son) was the repentance.

He was glad existence a Godfather of the operation with the music score past Serge Prokofiev and told that information technology was "the all-time music of the three ballets Prokofiev has composed." Diaghilev commissioned libretto to Boris Kochno, choreography to George Balanchine and sets and costumes to Georges Rouault, a French painter, draughtsman, and printer, whose work associated with and .

The ballet'due south story based on the biblical parable written in the Gospel of Luke. Yet, Boris Kochno added much dramatic material and emphasized the themes of sin and redemption by catastrophe the story with the Prodigal'south return domicile.

Dance historian and an archivist Susan Au wrote about the ballet: "Adjusted from the biblical story, information technology opens with the dissipated's rebellious divergence from home and his seduction by the beautiful but treacherous siren, whose followers rob him. Wretched and remorseful, he drags himself back to his forgiving father."

Left: Serge Lifar and Ofelia Doubrovska in The Prodigal Son. Photographer unknown, undated. Credit to: Howard D. Rothschild Drove.

The Prodigal Son was enthusiastically received by both audition and critics. Information technology was 1 of Balanchine'due south first ballets to achieve an international reputation. Its eternal themes, expressive score, and abstract but thoroughly dramatic movement make it as modern, exciting, and powerful today as it was back in 1929.

Above: Maria Kowroski every bit The Siren and Joaquin De Luz as The Prodigal Son, New York Metropolis Ballet. Photograph: Paul Kolnik

The Prodigal Son was the last ballet of the Ballets Russes. Serge Diaghilev died in August 1929, three months after its premier in Paris, surrounded by his close friends—Boris Kochno, Serge Lifar, Coco Chanel, and Misia Sert. Subsequently his death, the Ballets Russes disbanded.

Iii years later the company was recreated under the same name, and Diaghilev's legacy extended far beyond. His leading dancers and choreographers opened ballet schools or founded ballet theaters. And his daring spirit of innovation and collaboration continues to inspire artists of all disciplines upwards to this day.

Created over a century agone, the productions of the Ballets Russes revolutionised early 20th-century arts and continue to influence cultural activity today.

Written on materials by National Gallery of Commonwealth of australia, Victoria & Albert Musem, London, The Red List, The Met Museum, cocked.cyberspace, En revenant de l'expo!, the making of markova.com, New York Metropolis Ballet, the daily.example.edu, Secrets of Nijinsky, picassolive.ru, gramilano.com and other sources.

Title analogy: Ballets Russes posters from jewelsdujour.com.

Source: https://arthive.com/publications/3221~Ballets_Russes_as_a_driving_force_of_a_new_aesthetic_of_the_20th_century

0 Response to "It Was the Ballets Russes That Influenced the Art of Fashion Internationally"

Post a Comment